Photo: Eduardo Bonces

Located approximately 241 kilometers from Bogotá, Colombia's capital city, lies a lake with more than 13 kilometers long, a significant water source that needs help.

By: Eduardo Bonces for Voices for Change Program by Colombo Americano and U.S. Embassy in Colombia

Tota Lake, a vital source of freshwater in Colombia, faces many environmental problems caused by human activities. Farming of spring onions, rainbow trout farming, and sewage are threatening one of the most important water systems in Colombia.

According to Corpoboyaca, today, approximately 2,500 hectares of the surroundings are used to grow spring onions, making the region a leading national crop producer. It also produces around 100 tons of trout.

The production of these without ecological supervision risks the distribution of water not only for the region's inhabitants but also for consumption in the country.

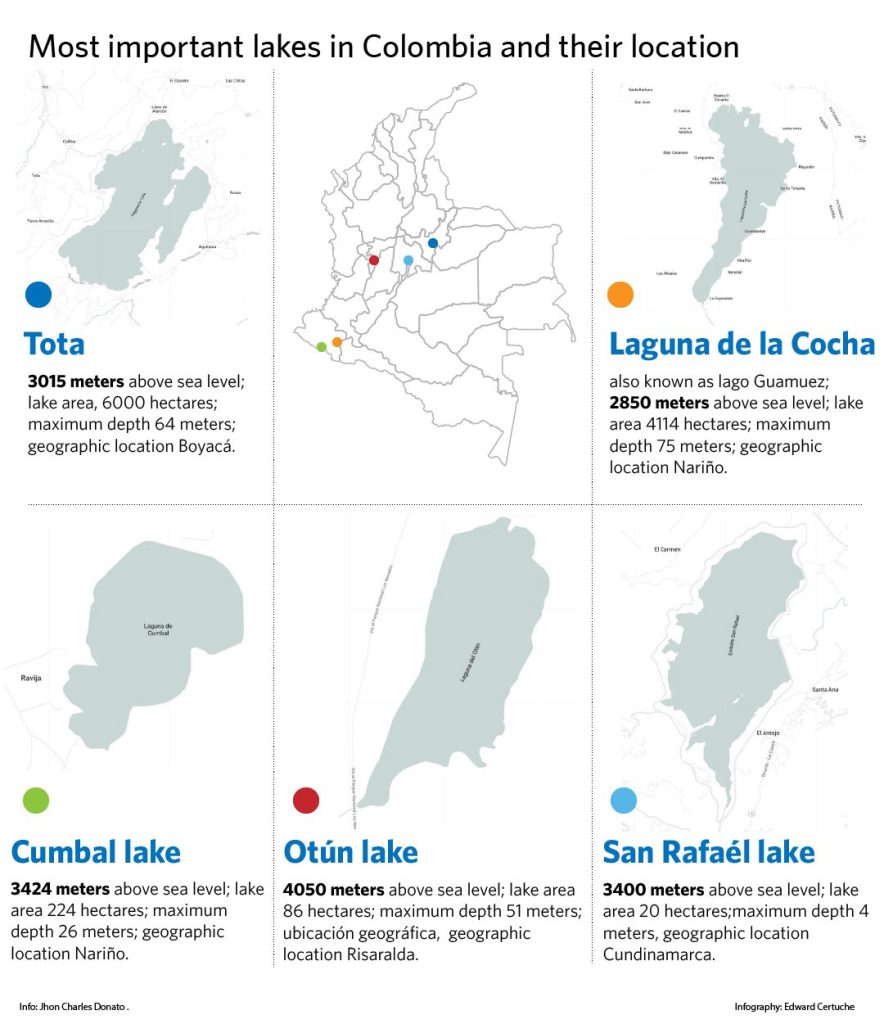

According to the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development, Tota Lake represents 13.55% of Colombia's freshwater supply and is a drinking water source for approximately 25,000 residents in the Boyacá Department.

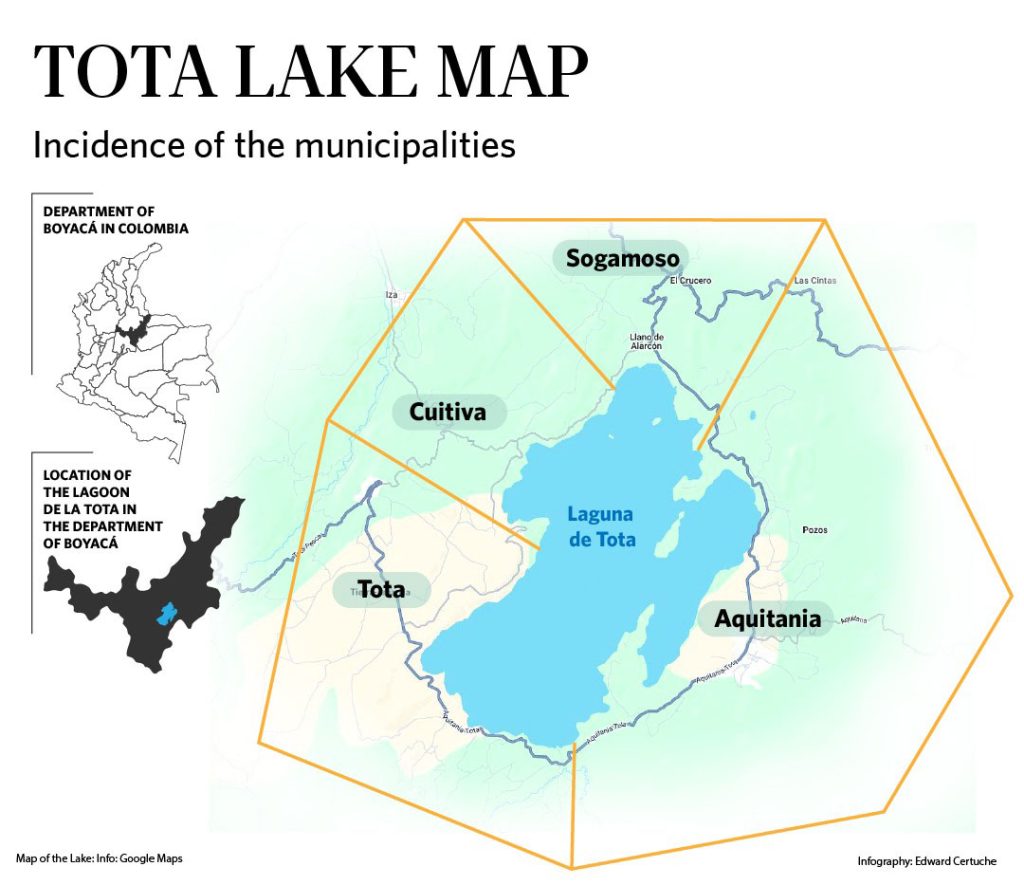

In other words, 20% of the department's population consumed water from Tota, which is represented by eight municipalities: Aquitania, Tota, Cuítiva, Iza, Firavitoba, Sogamoso, Nobsa, and Tibasosa.

Water Contamination

Colombia signed the Ramsar Convention, also known as "The Convention on Wetlands," in 1998 and participated in COP 13 about Wetlands, Tota, as a strategic water system still has not been postulated to be protected.

According to Mr. Nelson Aranguren, from Boyacá, an associate teacher from Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia (UPTC), "It hasn't been easy to include Tota Lake in the Ramsar convention because it is an agreement with the local community to take care of the water resource. But, some actors feel their interest must be affected".

Waves (Wealth Accounting and the Valuation of Ecosystem Services,) an international alliance led by the World Bank that promotes sustainable development, published a report about Colombian 2016 that indicates: " In 2013, the fishing industry emitted 24% of the Nitrogen total emissions to the Lake, and onion crops contributed 61%. Sewage, produced in close rivers, accounts for 15 % of this element".

Mr. John Charles Donato Rondón, Director of the Biology program at Universidad Nacional de Colombia, declared that one of the Lake's most significant problems was the green onion crops grown without supervision. "They used an organic fertilizer called 'gallinaza,' which is chicken manure, sometimes without any treatment. It is an excellent nutrient source for the crop, but it also causes a lot of environmental damage."

He also says that "green onion crops need a lot of nutrients and water supply. However, the environmental impact of the "gallinaza" had not been estimated. But I have some data that indicates that they are using a little bit more than 50 hectares of "gallinaza" per year, and the problem is that all that ends up in the waters of Tota, and it makes easy the eutrophication."

According to all experts, eutrophication is a process of high algae and aquatic plant growth thanks to the high levels of nitrogen and phosphorus in the water. This phenomenon could end with the reduction of the size of the Lake.

There is no recent research because carrying out these studies is expensive. However, Waves' evaluation in 2013 indicates that Tota phosphorus emissions are also disturbing. The fishing industry contributes 28%, sewerage 25%, and Onion crops 47% of this element.

Ms. Adriana Janneth Espinosa Ramírez, an expert in aquatic toxicology and environmental health at UPTC University, claimed that "the change in the Lake due to agricultural activity generates extreme pressure towards the dominance of undesirable microorganisms such as cyanobacteria. Currently, certain sectors of the Lake already have a high presence of them, which changes the trophic condition of the Lake and threatens the quality to purify."

Cyanobacteria are also a deep concern. Mr. Aranguren states, "These bacteria generate Cyanotoxins that can cause metabolic problems for fish, insects, and other organisms. The growth of cyanobacteria is not too short-term, but it could have an effect in the long term in humans."

Waves assure that "annually, 147 tons of nitrogen reach the Lake, of which approximately 83 tons is a by-product of spring onion farming. Likewise, almost 25 tons of phosphorus are deposited yearly, around half of which results from the same activity (between 10 and 13 tons per year). Sewerage systems emit between 7 and 8 tons of phosphorus per year.

A problem can Fly

Tota is considered a fundamental ecosystem for the development of some birds. According to Corpoboyacá, in the surroundings of the reservoir, more than 150 bird species have been seen, 116 of which are residents and 33 of which use the Lake as a resting place after large migrations during the boreal and southern winter. The Lake provides shelter and food for migratory birds.

The lake is also shelter for five menaced species as: the “Cucarachero de pantano”; Tingua de pico verde; Pato rufo; Rascón andino; and Alondra cornuda. They all needed the "juncal" plant that had been disappearing due to the lake conditions.

Claudia Yaneth Rivera Torres, an ornithologist who works at Corpoboyacá, the institution that manages the environmental problems in the department, reports that to recover the birds' habitat, it is necessary to "recover the Juncal that covers the edge of the Lake. Recover and maintain the water quality of the Lake. Avoid overuse of motorboats on the Lake, and be very responsible with managing solid waste such as plastics, bottles, and Styrofoam boxes, especially from agricultural materials."

On the other side of the Lake

Aquitania is the municipality with a significant portion of the Lake, and it also has more inhabitants who live from spring onion production. They all know how to produce, care for, and harvest it, a situation that doesn't let the crop end.

"This helps many families, and the municipality has been developing thanks also to the spring onion crop. We know we are trying to implement better practices, but the market has the last word", says Juan Montaña, a peasant of the region.

In Corabastos, Colombia's biggest goods market, the price of spring onions is determined by their thickness. Bigger means expensive, but more chemical products are used during crop growing.

Victor Manuel Riveros, an inhabitant of the Daitó village in Aquitania, Boyacá, says, "In all agricultural products, the consumer buys what looks best. If we come to reality, the best onion is the thinnest; it has the best flavor and fewer chemicals. But changing the mind of around 30 million people who consume it daily is very difficult."

Riveros denounces that when peasants produce in an agroecological way, their products have no market: "When I produce cleanly, I have no market, or they want the price to be lowered a lot. To produce an onion with good practices, I need about four months, which is different from what happens with mass-produced onions produced in two."

Mr. Javier Antonio Acevedo, an inhabitant of the municipality of Aquitania, Boyacá, and director of Tota Lake Museum, says that "there are some products that have undergone reconversion, but in the large market there is no specialized market for agroecological products with good agricultural practices, which not only sells them but also ensures that the buyer knows the traceability of the product."

However, the problem is economical; as Mr. Nelson Aranguren, leader of the research group "Aquatic Systems' Ecology Unit," summarizes, "the problem of ecosystems seems to be outside in the society in general. Beyond saying that the culprits are the onion growers, those from Aquitania, and the fish farmers, that is untrue. The problem belongs to society in general; society is connected directly with these problems. Why are onions still grown? Why have these crops' dynamics never changed? That cultivation was done twice a year, and now it has doubled; why? Why do fish farmers want more river licensing? The answer to all that is because those activities are profitable".

He adds that "the pilots that have adopted sustainable agriculture are stopping to use chicken manure and pesticides, and the profitability of these production processes is meager. So, these products don't have a market to buy them, or people don't consume them because they are so expensive. An organic onion is thinner and smaller than the other, but in society, the issue of economic cost takes precedence over the issue of environmental sustainability and health."